"I play, work and live thanks to the chip in my head": the first Neuralink patients break the mold

Half a century of research is finally yielding results: brain implants are coming out of the shadows of laboratories and starting to change people's lives. The most striking example is Noland Arbaugh, Elon Musk's first Neuralink patient. Paralysed after a water accident, he first played with the chip and now edits websites, sends emails, does banking, and is regaining his independence.

Neuralink has already implanted its devices in seven people, allowing them to control computers and even work. One of the users, Mike, is now a full-time research technician working from home. Alex, a former parts assembler, creates 3D components despite losing the mobility of his arms.

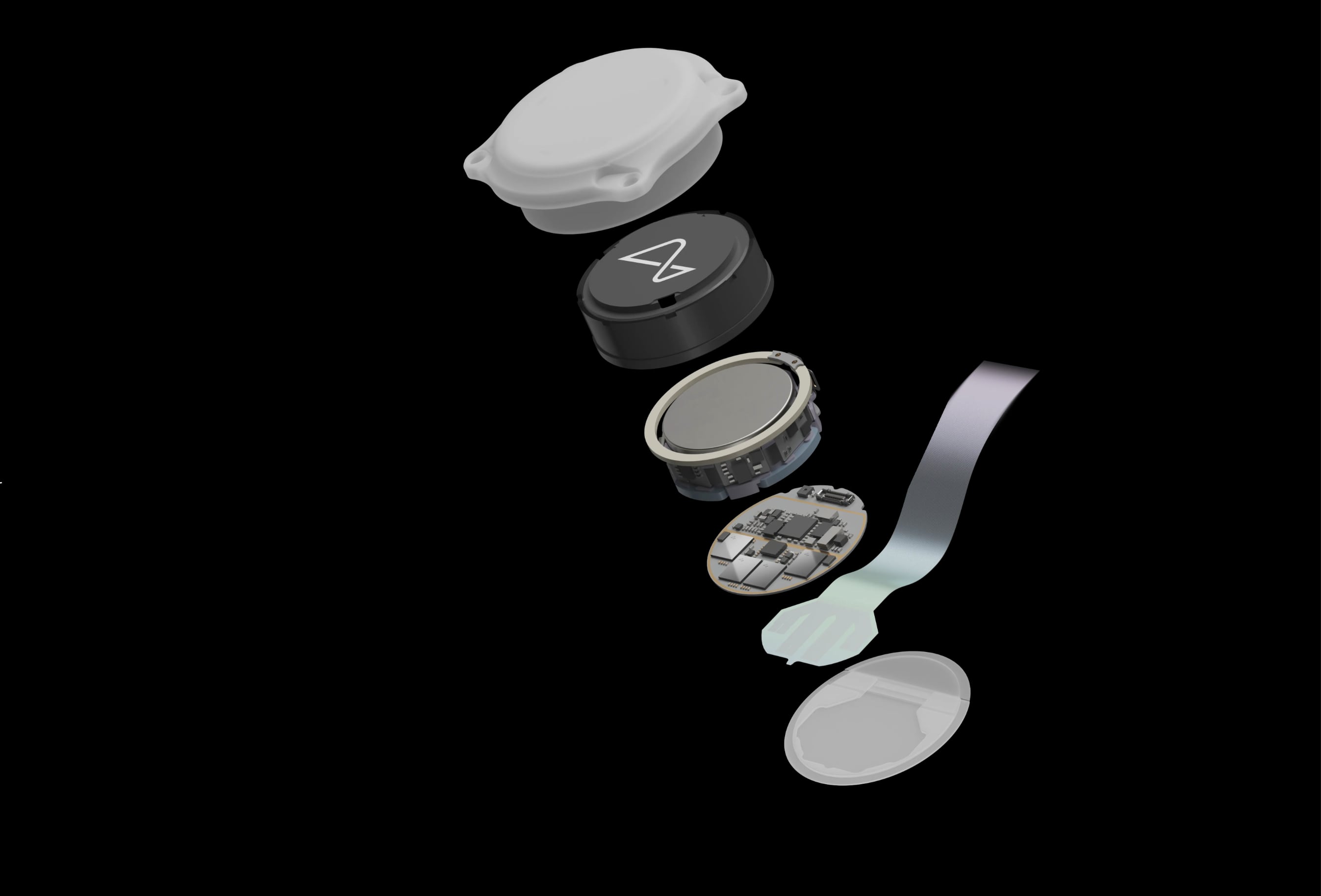

A Neuralink implant. Illustration: Neuralink

Why it matters

From experiments to real life: for the first time in a decade, BCI devices are moving beyond the lab and are actually restoring the ability of people with paralysis to work and communicate. This is not just about Neuralink, as competitors are already offering less invasive and more versatile solutions, from chips on the surface of the brain to those injected through blood vessels. The speed and scale are also impressive: UC Davis is turning thoughts into speech in 10 milliseconds, and Synchron is preparing a Bluetooth connection to the iPhone. Along with restoring independence for people with severe injuries comes the social implications - a potential transformation of human capabilities for tomorrow. But the prospects are also accompanied by ethical challenges: privacy, data security, and the limits of brain upgrades require serious attention today.

Competitors are coming

Neuralink is not alone in the race. Paradromics has just performed the first implantation of its 1,600-electrode chip (compared to Neuralink's 1,024). Precision Neuroscience offers less invasive thin films, and Synchron, backed by Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, has already implanted 10 people with devices that don't even require opening their skulls. Their chip will soon become the first Bluetooth BCI for Apple devices.

But there are nuances

Technology is still far from perfect. The UC Davis system is wrong in 44% of words, and manufacturers still have to solve the problems of security and privacy of neurodata. Nevertheless, optimism is growing: the first commercial products for people with spinal cord injuries or ALS are expected to be launched in 2-3 years.

What's next?

Arbo believes that one day BCI will become as commonplace as a smartphone. But right now, for him and other testers, these chips are not about cyberpunk fantasies, but about the return of simple human things - freedom of movement and the ability to live independently.

Source: qz.com