Batteries have long been the nervous system of the modern world: from smartphones that keep us online to wearable gadgets that monitor our health and giant energy storage systems that support renewable energy. In 2024, global battery demand exceeded 1 TWh and prices fell below $100/kWh - a symbolic milestone that opened the door to the mass electrification of transport and gadgets. But behind this success story lies a much more challenging future: from resource constraints to the race for new chemical formulas that can make batteries cheaper, safer and more durable.

Today's battery market resembles an arena for high-tech gladiators. Lithium-ion batteries remain the protagonists thanks to their proven reliability and scalability - they power 85% of electric cars, most smartphones and wearables in the world. But even in this segment, there is a chemical war going on: cheaper and safer LFP (lithium iron phosphate) is up against powerful but more expensive NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) and NCA (nickel cobalt aluminium) with a high nickel content. The Chinese giants CATL and BYD not only dominate the market(55% of the global share), but also push the industry towards engineering breakthroughs such as Blade Battery and Shenxing fast charging.

At the same time, next-generation technologies are maturing in laboratories: solid-state batteries for premium EVs, sodium batteries for low-cost solutions, graphene anodes for smartphones and wearables, lithium-sulfur prototypes for drones, and even futuristic metal-air systems for aviation. The main question is: which of these technologies will have time to overcome all the "childhood diseases" by 2030?

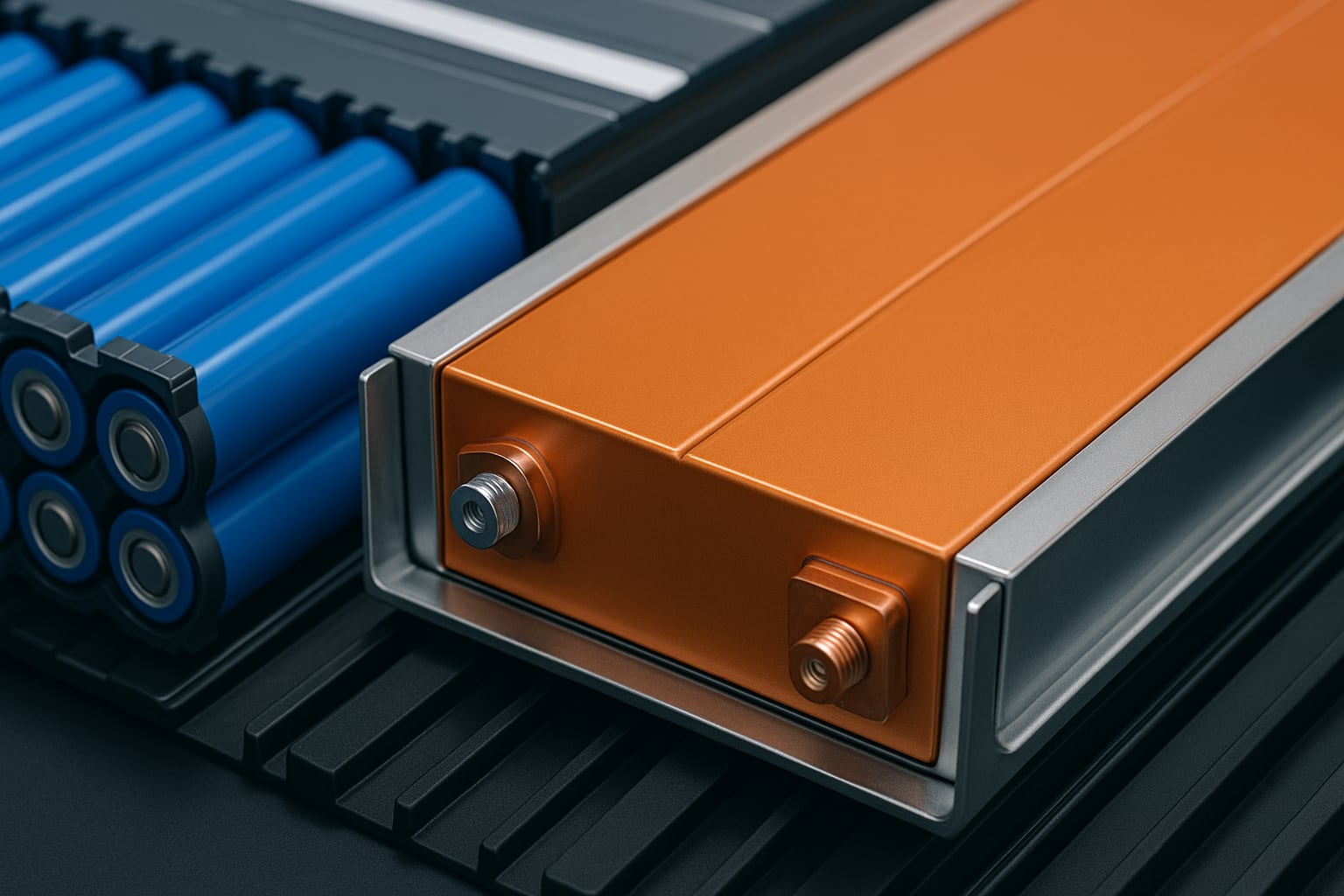

Lithium ion: the king who still holds the throne

Illustrative image of a lithium-ion battery. Illustration: DALL-E

Lithium-ion batteries are a classic that stubbornly refuses to leave the stage. They evolve, squeezing the most out of their chemistry through engineering tricks and new materials. Today, the two main schools of thought have come together in a duel: LFP versus NMC/NCA.

LFPs are cheap, durable, and safe - they are less prone to fire and can withstand up to 5,000 charging cycles. That's why Tesla puts them in standard models, and Chinese manufacturers rely on them for the mass segment. NMC and NCA, for their part, hold premium positions: higher energy density (200-260+ Wh/kg) allows EVs to cover more kilometres on a single charge. These are the batteries used in the best charging stations. However, these batteries are more expensive and dependent on unstable supplies of cobalt and nickel.

To overcome these limitations, market players are introducing structural innovations. BYD with its Blade Battery uses CTP (Cell-to-Pack), where the cells are integrated directly into the battery body. CATL has gone even further with the Shenxing LFP, promising to add 400 km of range in 10 minutes of charging and a range of over 1000 kilometres. Western companies are still lagging behind in terms of development speed and scaling, but are actively experimenting with anodes with silicon and even graphene to increase capacity.

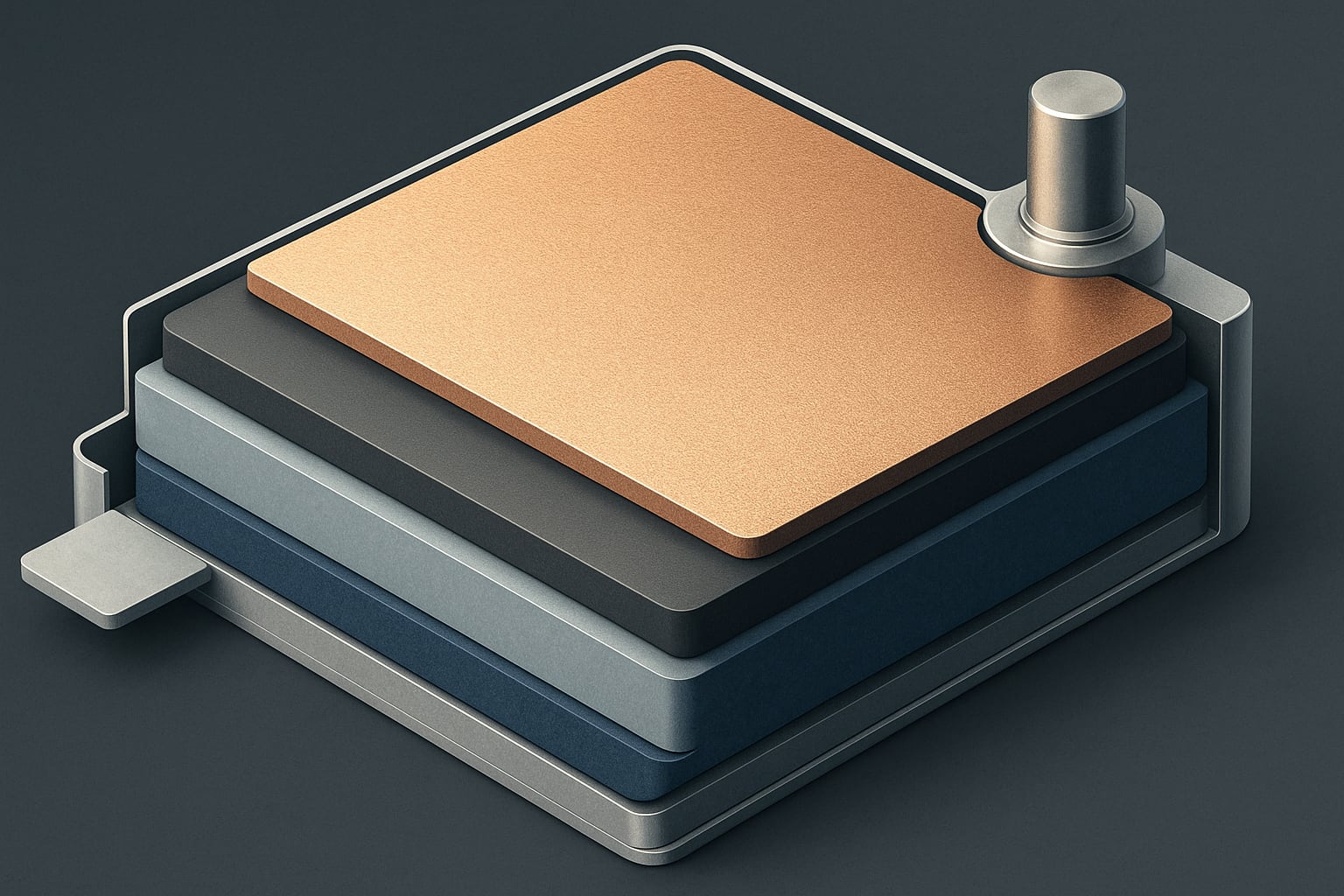

Solid-state batteries: the holy grail or just another promise?

Illustrative image of a solid-state battery. Illustration: DALL-E

Solid-state batteries (SSBs) have been the stuff of legend among engineers and car enthusiasts for several years now. Almost everyone promises them: Toyota, Volkswagen, Samsung, QuantumScape - each with their own vision. The basic idea is simple and revolutionary at the same time: to replace a flammable liquid electrolyte with a solid one to create a battery that charges in minutes and allows EVs to travel up to 1,000 km on a single charge.

The solid electrolyte paves the way for the use of lithium metal anodes, which provide an energy density of 350-500+ Wh/kg. For comparison, the top Li-ion batteries today are at the level of 250-300 Wh/kg. In addition, the absence of liquid components means greater safety - no thermal runaway and no fire shows in case of damage.

But there is a gap between theory and reality. Problems with scaling up production, the fragility of materials at the anode-cathode interface, high price and limited service life stop SSBs from entering the market on a mass scale. Toyota announces the first production cars powered by SSB by 2027, QuantumScape vows to provide samples for customers right now, but sceptics remind us of dozens of "breakthroughs" that have remained in press releases.

Sodium batteries: a budget contender

Illustrative image of a sodium battery. Illustration: DALL-E

While lithium continues to rise in price and geopolitical games threaten the stability of supply chains, sodium is entering the arena. Sodium batteries (Na-ion) do not require cobalt, nickel or even lithium - their protagonist has long been in your kitchen in the form of salt. This makes the technology cheaper and more resilient to global supply disruptions.

The main advantage of Na-ion is the availability of raw materials and good performance at low temperatures, which is ideal for energy saving and two-wheeled vehicles. However, there is also a weakness: lower energy density (∼140-160 Wh/kg), which does not yet allow it to compete with lithium-ion batteries in the premium segment of electric cars.

The most active players are the Chinese giant CATL, which has already introduced Li-ion + Na-ion hybrid batteries, and Natron Energy with its blue battery for data centres and stationary systems. Analysts predict that by 2026-2027, sodium solutions will take a significant market share for budget EVs, stationary storage, and low-power devices.

Graphene batteries: a myth or the next breakthrough?

Illustrative image of a graphene battery. Illustration: DALL-E

Graphene has been on the list of "revolutionary" materials for batteries for about ten years now, but so far it has been more of a buzzword in press releases than a mass product. Why is there so much noise around it? Graphene is an ultra-thin (one-atom) layer of carbon with incredible electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and mechanical strength. Add to this a huge surface area, and you get an ideal material for anodes that can potentially speed up smartphone charging by up to several minutes and increase battery capacity.

However, there are nuances. Mass production of high-quality graphene is still expensive and difficult, and anodes based on it lose stability during charging and discharging cycles. The industry is testing graphite + graphene hybrids to increase conductivity without the risk of rapid degradation. The first samples of such batteries are already being used in wearable devices and smartphones, but they are still a long way from automotive scale.

If engineers overcome these barriers, graphene batteries could become a dark horse of the market: ultra-fast charging, high capacity and longer durability are tempting for both smartphone manufacturers and EV giants.

Lithium-sulfur and metal-air batteries: niche superheroes

Illustrative image of a lithium-sulfur battery. Illustration: DALL-E

Lithium-sulphur (Li-S) batteries promise to become champions in terms of energy density - theoretically up to 600 Wh/kg, which is twice as much as the best lithium-ion solutions. They are cheaper to produce (sulphur is literally a by-product of oil refining) and more environmentally friendly due to the absence of cobalt. But there is a serious pitfall: the so-called "shuttle effect". This is a phenomenon where sulphur particles migrate between the anode and cathode, rapidly degrading the battery and reducing the number of charging cycles.

Metal-air batteries (lithium-air, zinc-air, aluminium-air) sound like science fiction. They can theoretically reach an energy capacity of more than 1,000 Wh/kg, because their "cathode" is oxygen from the atmosphere. This makes them ultralight and attractive for aviation, drones, and even military applications. In practice, however, problems with recharging and degradation have kept them at the level of laboratory prototypes.

Right now, these technologies are more of a niche market, but if their "childhood diseases" are cured, they could open up new horizons where weight and volume are critical.

pageHow AI and recycling are changing the life of batteries

An illustrative depiction of the use of AI in battery design and recycling. Illustration: DALL-E

In a world where gigafactories churn out hundreds of gigawatt-hours of batteries a year, the question of what to do with used batteries has become a painful one. New trends are entering the arena: artificial intelligence, recycling and reuse, and the concept of the circular economy.

Go Deeper:

Circularity is a buzzword from economists and environmentalists, but if we simplify it to human language, it means a "closed cycle of resource use". It means not "produced → used → thrown away", but "produced → used → recycled → used again".

AI is already changing the rules of the game at the development stage. Machine learning algorithms help to find new materials for anodes and cathodes, predict cell degradation, and optimise production processes. Microsoft and PNNL have recently discovered a new cathode material, N2116, thanks to an AI approach. And "digital twins" allow testing battery models before physical production, saving years of R&D.

At the same time, the EU is already introducing mandatory "battery passports" and recycling requirements. New recycling technologies - from pyrometallurgy to hydrometallurgy and direct reuse of materials - allow up to 95% of valuable metals to be recovered. Add to this the trend towards the "second life" of EV batteries in stationary power systems, and you have a shift from batteries as a "consumable" to batteries as an asset that can be restarted again and again.

What's next: a map of the battery future for 2025-2030

An illustrative depiction of the future of batteries. Illustration: DALL-E

The next five years for the battery industry will be like a chess game with several players and hundreds of pieces. Analysts' forecasts paint a diversified future where no single technology will be able to "take the throne".

Solid-state batteries have a chance to debut in the premium segment by 2027, but due to their high price, they are unlikely to quickly displace their lithium-ion counterparts. Sodium solutions will be actively promoted in stationary energy storage and low-cost transport, where energy intensity is not critical. Graphene and lithium-sulphur batteries are still dark horses - they may make a splash or remain niche for drones and aviation.

Recycling and reuse are also in the spotlight: Europe and the US are already introducing mandatory recycling rates, and China is actively investing in the "second life" of EV batteries. For manufacturers, the strategy for survival is simple: a portfolio of different technologies, their own supply chains, and localised production.

Table: Assessment of next-generation battery technologies

| Technology | Key advantage | Main limitation | Energy intensity (Wh/kg) | Technology readiness level (TRL) in 2025 | Target application | Key players |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-ion (LFP) | Low cost, safety, long service life | Average energy intensity | 160-210 | 9 (Commercial) | Mass EVs, grid energy storage | CATL, BYD |

| Lithium-ion (NMC) | High energy intensity | Cost, risks of material supply | 200-260+ | 9 (Commercial) | Premium/long-range EVs | LGES, SK On, Samsung SDI |

| Solid state (SSB) | Safety, high power consumption | Production scalability, cost | 350-500+ (target) | 6-7 (pilot/demo) | High-performance EVs | Toyota, QuantumScape, Samsung |

| Sodium (Na-ion) | Available, inexpensive materials | Lower energy intensity | 75-175 | 8-9 (Early commercial) | Energy storage, low-cost EVs | CATL, Natron Energy, HiNa |

| Lithium-sulphur (Li-S) | Very high specific energy, low cost | Poor service life (shuttle effect) | 450-600 (prototype) | 5-6 (laboratory/prototype) | Aviation, drones, electric aircraft | KERI, Zeta Energy, Gelion |

| Metal-air | Highest theoretical energy density | Poor reversibility, short service life | >1,000 (theoretical) | 3-4 (Fundamental RD) | Long-term EVs, aviation | Various research institutes |

Bottom line.

The future of batteries is not a story about a single "perfect" chemistry, but about a whole arsenal of technologies for different applications. The lithium ion will continue to be a workhorse for electric vehicles, smartphones and wearables for a long time to come. Sodium batteries are creeping up on the market as a low-cost solution for stationary systems and mass-market EVs. Solid-state variants, graphene anodes, and lithium-sulfur prototypes are still balancing between the "holy grail" and the long road from the lab to the assembly line.

At the same time, the industry is learning to live by the "nothing is lost" principle: AI is looking for new materials, and recycling and reuse are becoming a must-have for gigafactories. The next decade will show which manufacturers will be able to combine the speed of innovation, environmental friendliness, and stability of supply. After all, the game in the battery market is not won by the one who creates the most powerful battery, but by the one who can scale it to millions of devices.

For those who want to know more

- "They're coming": how humanoid robots are storming factories, warehouses and our hearts

- What slows down self-driving cars

- G-SHOCK and XG - how Casio changed its course from "survival watches" to neon style for the TikTok generation

- From failed rice cooker to PlayStation triumph: the story of Akio Morita

- How conspiracy theories led to the hacking of NASA servers and ruined the life of a sysadmin: the story of Gary McKinnon